Which Keyword Design Increases The Click And Purchase Probability

Abstract

Section titled “Abstract”In online retail, the majority of consumers use a search engine before making a purchase decision. Search engine advertising is important for the commercial use of a search engine. This study analyzes the infuence of content-related, formal and competition-related criteria for the keyword design on click and purchase probability. Using logistic regression, we analyze the click and purchase probabilities of various keywords based on an extensive data set from an e-commerce retailer. The empirical study shows that keyword specifcity and quality positively impact click and purchase probability, while the number of product details and the distance of a bit have a negative efect. Two of the three formal design criteria show little to no signifcant infuence on the target variables. The results provide advertisers with insights into how they should design their keywords. They should pay particular attention to the content-related keyword design criteria and the quality of the keyword.

Keywords Keyword design · Search engine advertising · Design criteria · Click probability · Purchase probability

1 Introduction

Section titled “1 Introduction”The utilization of search engines has become a pervasive practice among internet users, particularly in the feld of online retail. The majority of consumers engage with search engines prior to fnalizing the purchasing decisions, employing various keywords to fnd the right products and services [13, 35]. Beyond Google, numerous enterprises have discerned the business potential inherent in search engines, leading to the widespread adoption of paid search advertisements in recent years. Refecting this trend, global spending on digital advertising experienced a notable growth rate of 10.8%, reaching US$209.7 billion in 2022 [31]. This statistic underscores the increasing signifcance of this advertising modality.

In the area of search engine advertising (SEA), companies have the opportunity to bid on certain keywords and thus enable their services to be displayed in the paid search results. The chosen keyword serves as a connecting link between the advertiser and the user of the search engine [56]. Consequently, the efcacy of keyword generation assumes a pivotal role in SEA [34, 35, 52]. Even though it is important to know which keywords consumers use for their searches, a prevalent approach among advertisers involves relying on subjective insights to incorporate relevant keywords [29, 35, 60]. Advertisers enjoy the autonomy to determine the quantity and selection of keywords to promote. This has resulted in instances where large companies bid on hundreds of thousands of keywords concurrently [2, 35], despite the fact that a company’s top 20 most frequently searched keywords account for over 90% of its searches, clicks, and conversions. Consequently, the use of imprecise keywords contributes to wasted impressions, restricted ad reach, and escalated costs [26]. Evidently, the design of keywords assumes particular signifcance for the success of SEA [48].

Henceforth, scholars have delved into the pursuit of optimal keyword design since the inception of search engine utilization. Over time, the economic need to develop profcient and cost-efective keyword design has become increasingly evident. A large number of existing studies focus on investigating the substance of keywords and explore aspects such as the infuence of brand-related keywords [e.g., 16, 21, 25, 42, 43, 47, 58, specifc versus generic keywords [e.g., 40, 42, 53, and hedonistic versus utilitarian keywords [58]. Plenty of other research looks at the design of keywords based on their length, focusing on the application of long-tail theory [e.g., 1, 6, 35, 48, 49.

Another approach for scientifc studies is the quality of keywords. In this area, researchers have investigated the infuence of keyword quality for the allocation of advertising space [3, 25], on the click-through rate [61], on the cost per click [3, 25], and on the number of impressions, clicks, and conversions [3]. Prior investigations into keyword bidding have examined its efects on ad position or rank [18, 42], as well as costs, click-through rates, and conversion rates [5, 18, 37]. In the context of optimal keyword design, the studies not only include content-related and formal design criteria, but there are also studies on competition and click costs [e.g., 9, 40, 53.

However, none of these investigations addresses the relationship between the bid and the average maximum bid of the keyword, despite the plausible assumption that keywords have diferent probabilities of being clicked or prompting a purchase depending on the bid associated with the keyword. To address this gap, we introduce the novel variable distance of the bid.

Against this background, the aim of this study is to investigate the efects of various keyword design criteria on key economic indicators in the context of search engine advertising. The analysis includes content-related, formal and competition-related design criteria and considers their infuence against the theoretical

background of the buyer’s journey. Using an extensive dataset from a German B2B online retailer, a logistic regression analysis is employed to examine the impact of various design criteria on target variables pertinent to search engine advertising.

On the one hand, the click is included as a binary coded target variable in order to refect the economic beneft of search engine advertising. This model is intended to clarify whether and in what way the design criteria of the keyword have an infuence on the click probability. On the other hand, purchase is assumed to be another binary-coded target variable. This second model is intended to provide information on how the keyword design criteria afect the sale of a product. The independent examination of these two models confers advantages, as it facilitates inferences regarding which keyword design factors predominantly contribute to the prediction of either clicks or purchases. The following two research questions arise from the mentioned points.

Research questions:

-

- Which impact do the design criteria have on the click probability for a specifc keyword in the context of search engine advertising?

-

- Do the design criteria also have an infuence on the purchase probability regarding a specifc keyword?

The primary goal of this study is to answer the research questions and thereby provide recommendations for optimizing keyword design in the area of search engine advertising with regard to the two target variables mentioned above. To achieve this objective, after presenting the theoretical background as well as the literature review, hypotheses regarding the efect of possible infuencing factors on the click and purchase probability of search engine users are formulated. The subsequent empirical study goes beyond previous research on keyword design in the context of search engine advertising.

2 Theoretical background

Section titled “2 Theoretical background”2.1 Design criteria for keywords

Section titled “2.1 Design criteria for keywords”In the context of this investigation, the design criteria for keywords are systematically classifed into three overarching categories: content-related, formal, and competition-related criteria. The subsequent sections provide brief explanations for each category.

2.1.1 Content‑related design criteria for keywords

Section titled “2.1.1 Content‑related design criteria for keywords”A keyword can consist of a single term or a combination of several terms that are categorized as either generic, brand-related or product-specifc. Generic keywords encompass broad terms related to selected products, topics, services, or industries without specifc details [10, 18]. Typically, these keywords exhibit a substantial

search volume and face intense competition [22, 59], accompanied by a wide reach that exposes the advertised content to numerous users, particularly at the initial stages of a search engine query [45].

The literature does not provide a consistent defnition for brand-related keywords. According to Rutz and Bucklin and Rutz et al. [45, 46], brand-related keywords are those incorporating the name of the advertising company. Expanding on this defnition, Yang and Ghose [55] include keywords containing a manufacturer’s brand, a product brand, or brand-specifc information within the scope of brand-related keywords.

In the more advanced stages of the buying process, people utilizing search engines may use specifc keywords [4]. As outlined by Yang et al. [57], specifc keywords encompass article or serial numbers or provide a detailed description of a particular product. Rutz and Bucklin [45] similarly characterize specifc keywords as those that constrict or precisely describe a product.

2.1.2 Formal design criteria for keywords

Section titled “2.1.2 Formal design criteria for keywords”Quality as a decisive determinant for the economic success of a keyword, as auction results for each search query are not solely predicated on the bid but are augmented by weighted quality attributes [24]. In the context of the Google search engine, three central components have a signifcant infuence on the keyword’s quality score, as highlighted by Google [26]. Foremost among these is the anticipated click-through rate, denoting the likelihood that a user will click on the advertisement prompted by the keyword. A high probability positively impacts the quality score. Additionally, the criterion of ad relevance is integral to the quality score, assessing the alignment of the advertisement with the intent behind the search query. A strong correlation between the ad and the search query positively afects the quality score. The third and ultimate component shaping the quality factor is the user experience with the landing page. This component evaluates the landing page’s utility for the specifc keyword triggered by the search engine user’s query. If the website is classifed as useful, this has a positive efect on the quality factor and therefore on the quality score of the keyword [26]. To determine the ranking of an ad, the respective bid is multiplied by a quality score and sorted in descending order [51]. The resulting order then determines whether and in which position the ad is displayed. However, optimizing the quality factor is not an independent goal of search engine advertising, but an aid to achieve the business goals.

In addition to the quality of the keyword, the length of the keyword can also be subject to infuence by the advertiser. As posited by Kritzinger and Weideman [38], the length tends to be shorter for general keywords compared to more specifc ones. Due to the high information density of specifc keywords, these keywords often consist of several words and therefore belong to the category of long-tail keywords. Long-tail keywords are characterized by their extended length, typically comprising at least three or four words [38, 49]. They are much more precise in terms of content than short-tail keywords. However, search engine users often use short search queries with an average of 2.4–2.7 words per query [11].

The form of the keyword is susceptible to formal infuence not solely through its quality and length but also through the chosen keyword matching option, a determination made by the advertiser during keyword creation. It is possible to align the keyword particularly closely to the search term of the search engine user. In the case of the Google search engine, advertisers can select from three keyword matching options: “exact match”, “phrase match”, or “broad match” [27]. The distance between the keyword and the search query is greatest with the broad match option.

2.1.3 Competition‑related design criteria for keywords

Section titled “2.1.3 Competition‑related design criteria for keywords”Design criteria associated with competition are characterized by their dependence on the competitors participating in the specifc auction for ad spaces. The competition of a keyword is determined by the Google search engine using various factors. Within the keyword tool, Google specifes a value ranging from 1 to 100 to each keyword. While 1 stands for low competition for the keyword, high values up to 100 indicate high advertising activity for this keyword. The factors infuencing Google’s competition evaluation are not transparent to advertisers. However, it can be assumed that Google uses internal fgures that measure the occupancy of individual keywords to an advertiser’s bid. Generally, longer keywords tend to have lower competition, while those with a substantial search volume are anticipated to face heightened competition [17, 25].

Among the competition-related criteria, the distance of the bid also emerges as a notable factor. The performance of the keyword is often determined by the click price bid [19]. As the click price is particularly infuenced by the relevance and competition of a keyword [19, 20], it is necessary to examine not the absolute bid of the advertiser, but the bid in relation to the average maximum bid for the respective keyword. The distance of the bid is thus expressed as the diference between the average maximum bid for the keyword and the click price bid by the advertiser.

2.2 Literature review and research gap

Section titled “2.2 Literature review and research gap”With the advent of search engine advertising and search engine optimization, the imperative for developing a successful and cost-efective keyword design has gained prominence in both practical and academic domains.

To understand the impact of keyword design on the probability of clicks and purchases, it is also important to consider the buyer’s journey. The buyer’s journey consists of diferent phases that infuence how consumers respond to keywords and advertising strategies based on their current needs and attitudes. As the buyer’s journey comprises the decision-making process that a potential customer goes through before purchasing a product or service, it is important to analyze it in a targeted manner [36]. Usually a distinction is made between the phases: awareness, consideration, and decision. In the awareness phase, potential customers have a need or a problem that leads them to search for information. Various studies point to the importance of understanding consumer behavior at this stage in order to derive successful marketing strategies [7, 23]. With regard to search engine advertising,

this means that keywords that efectively highlight solutions to customers’ needs can attract attention and increase click-through rates. When potential buyers enter the consideration phase, their evaluations become more focussed. They actively compare diferent options, weighing up various factors such as quality, price and brand reputation. This critical analysis phase suggests that keywords must be tailored to refect competitive advantages and align with consumer evaluations [40]. Finally, in the decision phase, the focus on direct attributes such as product quality and customer reviews becomes increasingly relevant. The mindset of consumers is now more concrete, so their search queries also have a more concrete language [30]. Keywords that integrate aspects of trust and social proof, such as ‘top-rated’, could increase the probability of purchase. The power of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) supports this assumption, as it has already been shown that a positive brand image cultivated through e-WOM leads to higher consumer trust and clickthrough rates [44].

With a view to optimizing the design of keywords, numerous studies have focused on examining the content of keywords. Investigations have delved into the impact of hedonistic and utilitarian keywords [58], as well as the dichotomy between specifc and generic keywords [e.g., 40, 42, 53], on the efcacy of search engine advertising. The infuence of brand-related keywords has been a frequent subject of analysis [e.g., 10, 12, 16, 21, 25, 34, 42, 45, 47, 58].

Table 1 below presents an overview of the analyzed criteria for keyword structure and associated business objectives within the realm of search engine advertising. The key research fndings are then briefy explained. In addition, the present study is diferentiated from previous research.

Concerning content-related design criteria, empirical evidence indicates that generic keywords generate more ad impressions but result in lower click-through and conversion rates compared to more specifc keywords [22]. Although generic keywords may not directly contribute to increased sales, they can stimulate further brand-related searches by search engine users [45]. Divergent fndings exist regarding the performance of brand-related keywords. According to Fuchs et al. [22] and Du et al. (2017), brand-related keywords lead to signifcantly fewer impressions compared to generic keywords, but to more clicks. This results in a high clickthrough rate for brand-related keywords. Conversely, Ghose and Yang [25] demonstrate a decrease in both click-through and conversion rates when brand-specifc information is integrated into the keyword. The efects of specifc keywords on the economic parameters of search engine advertising have also been examined in a number of studies. Agarwal et al. [4] established a correlation between specifc keywords and a higher average click-through rate. Moreover, it has been observed that the inclusion of specifc keywords can enhance purchases of the advertised product and increase the conversion rate [18, 40].

In addition to content-related design criteria, the length of keywords has been extensively examined in previous studies, with a particular emphasis on the application of the long-tail principle [e.g., 1, 6, 35, 48, 49. Studies have shown that longtail keywords, characterized by fewer searches on average, exhibit signifcantly lower search volume and less competition [25]. Further research highlights that the application of the long-tail principle enables advertisers to capture niche markets

| Table 1 | Literature overview on keyword design criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| References | Keyword design criteria | Target variables |

| Ghose and Yang [25] | Keyword category, length of the keyword, quality of the landing page and cost per click | Impressions, clicks, orders, click-through rate and conversion rate |

| Ji et al. [35] | Position and length of the keyword | Click-through rate |

| Skiera et al. [48] | Long-tail keywords | Share of searches, share of clicks and share of conversions |

| Agarwal et al. [4] | Ad position and specifc keywords | Click-through rate and conversion rate |

| Rutz and Bucklin [45] | Generic and brand-related keywords | Impressions, clicks, reservations, costs (per day, per click and per reservation), click-through rate and conversion rate |

| Abou Nabout and Skiera [3] | Quality of the keyword | Click costs, clicks, advertising expenditure and revenue |

| Fuchs et al. [22] | Generic and brand-related keywords | Impressions, clicks, click-through rate, costs, conversions, conver- sion rate and ratio of costs to conversions |

| Atkinson et al. [9] | Criteria for designing ads (e.g. click costs, keyword category, title of the advert, etc.) | Click-through rate |

| Lu and Zhao [40] | Keyword category, product type, number of keywords, click costs, product price, reputation, number of products | Direct and indirect purchases |

| Yang et al. [57] | Competitive factors, demand factors and supply factors | Click volume, click costs, number of market participants and prob ability of companies entering the market |

| Narayanan and Kalyanam [42] | Keyword matching options, content of the keyword, content of the ad, day of the week, supplier size, experience with the supplier | Click-through rate and orders |

| Yuan et al. [61] | quality factor, expected click-through rate | Revenue |

| Amaldoss et al. [5] | Keyword matching options | Keyword management costs |

| Du et al. [18] | Keyword category, keyword matching options | click volume, number of sales, revenue |

| Wang et al. [53] | Mobile and online keywords, keyword category, click costs | Direct and indirect purchases |

| Cao et al. [12] | Keyword portfolio diversity and disparity (composition of e.g. brand, product type, function, appearance, etc.) | Direct and indirect purchases |

by targeting less competitive keywords. Empirical fndings suggest that a signifcant share of conversions can be attributed to niche keywords and that long-tail strategies can lead to lower costs [1, 6, 35, 48].

Another feld of research in the area of keyword design is keyword quality. In this context, the importance of keyword quality for the allocation of ad placements [3, 25], as well as its impact on cost per click and click-through rate [3, 25, 61] were analyzed. Optimizing the quality factor can help to obtain a competitive ad space despite having the same bid as competitors and to achieve more clicks and conversions at the same cost [61].

The literature review and the information presented in Table 1 reveal a notable gap in existing research concerning competition-related keyword design criteria. The current study addresses this gap by including competition-related design criteria in addition to content-related and formal design criteria. So far, there is no study that covers the relationship between the click price and the highest bid for a keyword. To bridge this gap, this study introduces the variable distance of the bid from the average maximum bid of the keyword, based on the assumption that keywords exhibit diferent probabilities of being clicked or leading to a purchase depending on the bid level. Moreover, this study extends previous research by quantitatively assessing the infuence of keyword design criteria on the dependent variables click probability and purchase probability, which have rarely been investigated to date. The fndings aim to ofer practical guidance for optimizing keyword strategies in paid search advertising by aligning bidding decisions with the user’s decision-making process.

As the empirical results on the infuence of the various design criteria are placed in the context of the buyer’s journey, the study also ofers a theoretical contribution. As potential customers are in diferent phases of the decision-making process, the requirements for keywords vary depending on the phase. A purely static examination of the keyword design criteria therefore does not appear to be appropriate. In the awareness phase, for example, broadly formulated keywords are more relevant due to the search for more general information. Whereas users in the decision phase are looking for much more specifc information. In particular, the literature review revealed a gap regarding competition-related keyword design criteria. Competitionrelated design criteria are important for the consideration phase, in which buyers compare diferent suppliers or alternatives. By mapping keyword design criteria to specifc phases of the buyer’s journey, the study provides a framework for understanding how user intent interacts with content and competitive factors. This theoretical integration not only contextualizes the empirical results, but also contributes to a more diferentiated understanding of keyword efectiveness.

3 Hypotheses development and research model

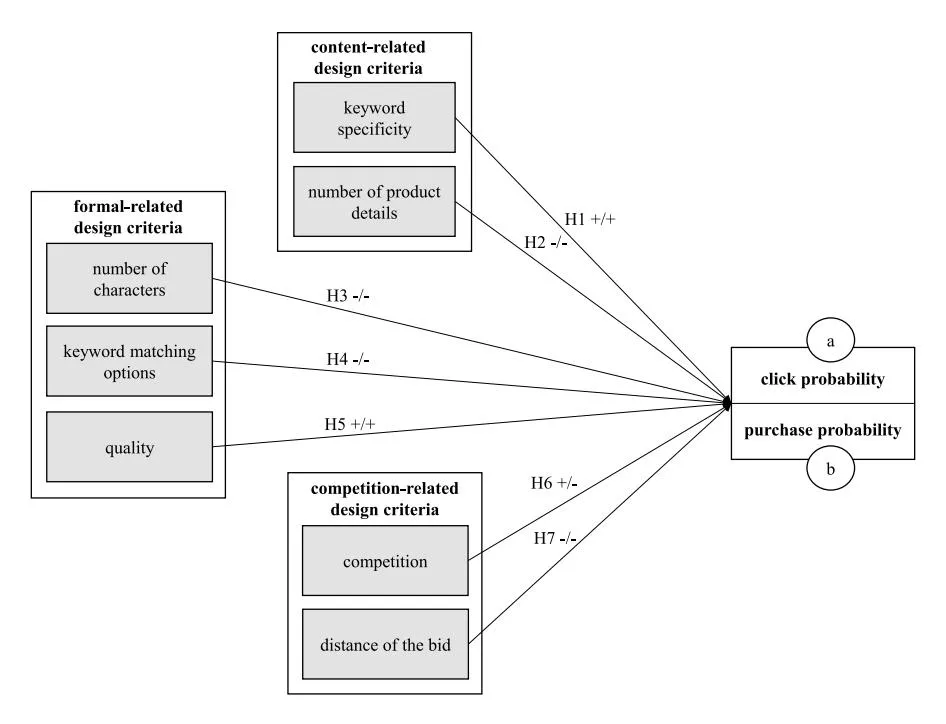

Section titled “3 Hypotheses development and research model”Considering previous research, hypotheses are derived below concerning the interdependencies between the various design criteria and the target variables. Design criteria encompassing content-related, formal, and competition-related aspects of keywords are taken into consideration. An infuence of these criteria is assumed both in terms of click probability and purchase probability.

3.1 Hypotheses on the content‑related design of the keyword

Section titled “3.1 Hypotheses on the content‑related design of the keyword”The initial aspect of content-related keyword design refers to the specifcity of the keyword. This specifcity varies, ranging from a generic identifcation of the product type to a more specifc mention of a particular product coupled with desired brand or other product-related details. The keyword specifcity can be used to determine at which search stage the search engine users should be addressed. At the early stages of their search, users typically seek a product type without intricate restrictions or detailed preferences. In contrast, users in advanced stages of the search process harbor more precise ideas about the product [10, 39]. They conduct more targeted searches, often seeking a combination of a product type, a specifc brand, and selected product-related details [54]. While generic keywords are initially employed by search engine users to gain an overview of available oferings, specifc search queries signify a concrete expression of interest [4, 40, 45]. This observation is supported by empirical evidence that generic keywords deliver more impressions than brand-related keywords, but lead to fewer clicks [22]. Consequently, the specifcity of the keyword tends to grow with the search engine user’s imagination, indicating proximity to the click and transaction [10, 33]. Thus, keyword specifcity can serve as an indicator of the user’s cognitive and emotional proximity to a transaction, mirroring their progression through the buyer’s journey. A higher degree of specifcity not only signals a clearer product vision but also corresponds to later phases in the decision-making process where both click and conversion probabilities are elevated. This suggests that an increasing keyword specifcity increases the click and purchase probability.

H1a A high keyword specifcity increases the click probability of the keyword.

H1b A high keyword specifcity increases the purchase probability of the keyword.

Distinct from keyword specifcity, the utilization of product details in a keyword introduces a diferent facet. With regard to the product details used in the keyword, the long-tail theory can be applied [6]. This states that keywords with a higher number of product details lose competition, but also generate a lower search volume [17]. This indicates that long-tail keywords, despite being less competitive, may not inherently attract more clicks if they fail to match users’ immediate search intentions [35]. The majority of search engine users tend to employ a limited number of specifc product details in their searches [49]. This predisposes advertisers to the risk that their keywords might be subjected to minimal or no searches which has a negative efect on clicks and conversions [48]. It can therefore be assumed that keywords become so specialized with an increasing number of product details that they are hardly ever searched for or clicked on. Moreover, Skiera et al. [48] confrm that although long-tail keywords can lead to conversions, the volume required for substantial campaign results remains a challenge. This points to a trade-of in the targeting strategy: although detailed keywords can be very relevant for users in the fnal stage of the buyer’s journey,

their extremely low frequency can reduce overall visibility and limit the efectiveness of advertising. Therefore, the use of too many specifc product details can lead to decreasing click and purchase probabilities, despite the theoretically high purchase intent of users in the decision phase. The above points lead to the following two hypotheses.

H2a A high number of product details in the keyword reduces the click probability.

H2b A high number of product details in the keyword reduces the purchase probability.

3.2 Hypotheses on the formal design of the keyword

Section titled “3.2 Hypotheses on the formal design of the keyword”In addition to content-related design criteria, formal design criteria can also exert infuence on the target variables. A formal design criterion of the keyword is the number of characters. An increase in the number of characters can be accompanied by an increase in words and information. Corresponding to the long-tail theory, the number of competitors and advertisers’ willingness to pay typically decrease as the number of characters per keyword increases [62]. This implies that the number of characters exerts a diminishing efect on the click price of the keyword. Despite the favorability of a low click price associated with an increased number of characters in the keyword, it is reasonable to presume a negative correlation between the number of characters and the click and purchase probabilities. Given that search engine users often use short search queries, averaging between 2.4 and 2.7 words [11], the tendency is towards a limited number of characters. However, if keywords with a high number of characters are used, this no longer corresponds to the general search behavior of most search engine users. As a result, the search volume is reduced. It can therefore happen to advertisers that keywords with an increasing number of characters become too specifc and are hardly searched for and clicked on. This in turn has a negative impact on the probability of purchase.

H3a A high number of characters in the keyword reduces the click probability.

H3b A high number of characters in the keyword reduces the purchase probability.

Advertisers have three diferent options to choose from for determining which type of search query their ad should be displayed for. These three options range from a strong proximity to a strong distance of the keyword from the search query of the search engine user. In terms of click probability, it can be postulated that a decrease occurs when the keyword, aligned closely with the chosen keyword matching option, diverges further from the search query. In this scenario, the number of impressions does not decrease, but the relevance of the keyword does [32]. Since the ads are also displayed when the search query is weakly related, the relevance of the ad for the searcher decreases and fewer searchers click on the ad [8]. This implies

that despite an increase in the number of impressions with an expanding keyword matching option, the reduced relevance of the ad leads to a decline in the number of clicks. In the consideration and decision phase, users tend to make more precise search queries that refect a clearer understanding of the product, so that more exact matching options are more likely to match users’ expectations and search behavior. For the above reasons, the following is expected:

H4a A large distance of the keyword from the search query reduces the click probability of the keyword.

H4b A large distance of the keyword from the search query reduces the purchase probability of the keyword.

The quality and the quality factor per keyword are determined by various aspects. One of the most important factors is ad relevance. Ad relevance serves as the search engine’s metric indicating the degree of relevance of an ad concerning search queries associated with a particular keyword [27]. If the search engine classifes the relevance and therefore the quality as high, the ad is displayed more frequently and the impressions increase. It can also be postulated that clicks increase with higher keyword quality, as the ad can be considered relevant for the searched keyword [41]. Based on this, it is assumed that a higher keyword quality has a positive efect on the click and purchase probability.

H5a A high qualitiy of the keyword increases the click probability. H5b A high qualitiy of the keyword increases the purchase probability.

3.3 Hypotheses on the competition‑related design of the keyword

Section titled “3.3 Hypotheses on the competition‑related design of the keyword”The determination of keyword competition by the Google search engine relies on a multitude of factors. It is suspected that Google calculates the competition based on keywords with associated bids. Keywords with many product details generally have less competition, but they also have a low search volume [17]. This suggests that keywords with high competition in particular have a high search volume, increasing the probability of being clicked on frequently. For the probability of purchase, however, a diferent direction of efect can be presumed. Increased competition expands the supply and selection while demand remains constant. The consequence is a reduction in the probability of purchase with rising competition. Integrating the perspective of the buyer’s journey, it can be assumed that high-competition keywords attract users in earlier search phases, where informational intent dominates. In contrast, low-competition keywords often represent the more specifc, action-oriented queries of users in the decision phase. So, while high competition correlates positively with the probability of being clicked, it could have the opposite efect on the probability of purchase.

H6a High competition for the keyword increases the click probability of the keyword. H6b High competition for the keyword reduces the purchase probability of the keyword.

Keywords with a high search volume are not only popular with searchers, but also with advertisers [17]. In order to obtain one of the few ad spaces in paid search, the advertiser must therefore bid more for the ad space than the other advertisers. This increases the average maximum bid to be paid per click on the keyword. For this reason, the bid of the individual advertiser should be oriented towards the average maximum bid of the keyword in order to be displayed and clicked. From the perspective of the buyer’s journey, aligning keyword bids with user intent becomes particularly relevant. Users in the awareness phase are less likely to convert and often use high-volume, generic keywords—where competition and bid levels tend to be highest [10]. In contrast, users in the decision phase typically use more specifc, lower-volume keywords that signal a strong purchase intent [30]. In these later phases, even a moderate bid that is close to the average maximum bid can yield a higher purchase probability due to the stronger transactional orientation of the user. Thus, the efectiveness of the bid strategy depends not only on the bid amount itself, but also on how well it aligns with the user’s stage in the decision-making process. It can therefore be assumed that both the click probability and the purchase probability decrease if the bid is far removed from the average maximum bid of the keyword.

H7a A large distance of the bid from the average maximum bid of the keyword reduces the click probability.

H7b A large distance of the bid from the average maximum bid of the keyword reduces the purchase probability.

Figure 1 graphically illustrates the research model along with the hypotheses derived.

4 Data and method

Section titled “4 Data and method”4.1 Data and operationalization

Section titled “4.1 Data and operationalization”The research dataset originates from a German online retailer catering to major customers in the clothing industry. With a decade-long presence in the online market, the retailer commenced search engine advertising on the Google search engine in late 2018. The dataset encompasses information on diverse keywords and their performance spanning a 2.5-year timeframe, from September 2019 to February 2022. Compilation and processing of the data were executed from multiple sources, integrating insights from the google ads tool and the keyword planner tool, both

Fig. 1 Research model

provided by Google. The keyword in combination with the date and time was used to combine the information from the various sources. In addition to information on the online retailer’s keywords, the data set also contains data on the keyword’s competitive situation.

The data set comprises a total of 823 diferent keywords, which achieved 753,965 impressions and 98,909 clicks. These keywords are composed of 76 diferent product types, each characterized by an average monthly search volume ranging from 590 to 135,000. The dependent and independent variables included in the study are operationalized below.

4.1.1 Dependent variables

Section titled “4.1.1 Dependent variables”The initial model employs the binary-coded variable click as the dependent variable. This variable delineates whether a keyword resulted in a click on the ad throughout the data collection period. Each clicked keyword is denoted by the value 1 within this variable.

The second model investigates the impact of design criteria on the probability of purchase. The dependent variable in this model is the binary-coded variable purchase. If a keyword results in a purchase, as recorded in the dataset through the conversion, it is assigned the value 1; otherwise, if it does not lead to a purchase, the keyword is assigned the value 0.

The descriptive statistics of the two variables show that 84.93% of keywords in the dataset were clicked. Additionally, 41.80% of all keywords led to a purchase. A comparative analysis reveals that approximately 50% of the keywords that result in a click also lead to a purchase. It is therefore particularly interesting to examine which keyword design criteria only infuence the click probability and which criteria also infuence the comparatively smaller proportion of purchases.

4.1.2 Independent variables

Section titled “4.1.2 Independent variables”As one of the content design criteria, the keyword specifcity indicates how specifcally a product is described within the keyword. This specifcity serves as a symbolic representation of various stages within the search process. A low specifcity is attributed when only the product type is mentioned, signifying a limited provision of additional details by the searcher. The pure naming of the brand is not considered, as only the specifcity of the product or the proximity to a specifc product should be considered in the analysis.

If a brand is mentioned in the keyword together with the product type, there is a medium specifcity of the product type. If further product information is added to the keyword in addition to the information about the product type and brand, the keyword has a high specifcity. The keyword specifcity can therefore have a value between one and three, as exemplifed in Table 2.

While keyword specifcity serves as a representation of the evolving stages in the search process by distinguishing various keywords for distinct phases, the variable number of product details quantifes the extent to which additional product details are incorporated into the keyword, beyond the specifcation of the product type and/ or brand. Product details are therefore additional information about a product that goes beyond the brand name and product type. The product details include the following information about the product:

- The article number

- The color

- The gender für which the product is intended

- The size

- The name oft the collection

- The material

- The product category

- The product details

Table 2 Example for determining the keyword specifcity

| Specifcity | Keyword content | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Low=1 Medium=2 High=3 | Product type Product type & brand Product type, brand, and product details | Sweatpants Fruit of the loom sweatpants Grey sol’s sweatpants |

Table 3 Example of the number of product details

| Color | Gender | Size |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| npdk= (2+1+1)=4 |

Table 4 Example of calculating the distance of the keyword from the search query

| Removal of the keyword from the search query | Keyword matching options | Search queries for the example “men’s jackets” |

|---|---|---|

| Low=1 | Exact match | Men’s jackets |

| Medium=2 | Phrase match | Buy men’s jackets |

| High=3 | Broad match | Men coat |

• The possible use

Section titled “• The possible use”As an example, the number of product details (npdk ) of the keyword “blue and white men’s pullover size XXL” can be calculated as shown in Table 3.

The formal design criteria of a keyword include the number of characters, the keyword matching options and the quality of the keyword. The number of characters (nock) considers all characters of a keyword.

nock = number of characters of a keywordk

ck,i = characters of a keywordk

j = number of characters

It is possible to align a keyword particularly close or far away from the search term of the search engine user. One of the three keyword matching options “exact match”, “phrase match” or “broad match” can be selected for this. While keywords with the keyword matching option “exact match” have almost the same meaning as the search query of the search engine user, the ads for keywords with the keyword matching option “broad match” are displayed even if they are only slightly related to the actual search query. This results in a ranking of 1 to 3 on the basis of the keyword matching options via the distance of the keywords to the search query of the search engine user. The keyword option exactly matching is given the lowest value 1 due to the lowest distance to the search term of the search engine user. To illustrate the keyword matching options, Table 4 shows the search queries for which the ad for the example keyword “men’s jackets” would be displayed.

Google’s quality factor comprises three integral components: the expected click-through rate, ad relevance, and landing page experience. The expected click-through rate indicates the probability that a user will click on the ad when it is displayed to him or her. If the probability is high, this has a positive effect on the quality score of the keyword. It is crucial to distinguish this component from the click-through rate, as the former is an estimation, while the latter is calculated by the search engine operator. Ad relevance assesses the alignment between the advertisement and the intention behind the search query. If there is a strong correlation between the ad and the search query, this has a positive influence on the quality of the keyword. The landing page experience evaluates the utility of the website concerning the specific search term. A classification of the website as useful contributes positively to the quality factor and, consequently, the quality score of the keyword. The quality of a keyword is quantified by the quality factor, which ranges from a minimum value of 1 to a maximum value of 10. A lower quality is indicated by a value of 1, while the highest attainable value for a keyword is 10.

The competition-related design criteria encompass the competition associated with the keyword and the distance of the bid. The distance between the bid click price and the average highest bid for the keyword is the difference between the two values. The average maximum bid is the average amount paid by advertisers to place their paid ad above the organic results on a search results page. to calculate the average maximum bid per keyword, all maximum bids for the respective keyword in the data collection period were added together and divided by the number of auctions. By subtracting the individual bids from the average maximum bid of the keyword, the distance of the bid is calculated. Positive deviations indicate a lower bid click price in comparison to the average maximum bid, while negative deviations signify a bid higher than the average maximum bid.

= distance of the bid from the average maximum bid of a keywordk

= average maximum bid of a keyword in the month t

= click costs of a keywordk

n = number of months

k = specific keyword

t = specific month

Using the formula, the distance of the bid for the example keyword “blue and white men’s sweater size XXL” would be calculated as shown in Table 5.

| Table 5 Example calculation of the distance of the bid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | -------------------------------------------------------- | — | — | — |

| Bid of the advertiser | Highest bid 1 of a previous auction | Highest bid 2 of a previous auction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.72 € | 1.02 € | 0.85 € | ||

| = (1.02+0.85) − 0.72 = 0. 22 € dotbk,t 2 |

4.2 Method

Section titled “4.2 Method”For the following empirical analysis of the factors infuencing the click and purchase probability of users of paid search, a logistic regression analysis is used as a method. The multivariate analysis method of logistic regression is one of the structure-testing methods. Unlike linear regression, it is suitable for examining relationships with nominally scaled dependent variables [15]. In this empirical study, the click probability serves as the target variable in the frst regression analysis. In the subsequent logistic regression, the purchase probability is used as the target variable. The independent variables can have a nominal, ordinal or metric scale level [14]. In this case, content-related, formal and competition-related variables are included in the study, which have a metric or ordinal scale level. The dependent variables have two values. Binary logistic regression is used for two values. The basics and preconditions for this method are briefy presented below.

Binary logistic regression is used to determine how the independent variables xj afect the probability of occurrence of the categories of the dependent variable yk. For this purpose, the regression coefcients bj of the independent variables are estimated [15]. In this case, for example, it is possible to determine how the keyword specifcity infuences the probability of a click or a purchase. In order to use logistic regression, a number of preconditions must be met. Special distribution assumptions are not necessary for logistic regression, but a sufcient sample size is required. For meaningful results, the sample size should be at least 100 observations [50]. Furthermore, there should be no high correlations between the independent variables (multicollinearity) and possible outliers should be identifed in order to prevent biased estimates [14]. If all preconditions are met, the unknown regression coefcients can be estimated using the maximum likelihood method. This is an iterative estimation procedure with which the estimates of the parameters should be selected in such a way that the probability of obtaining the observed data is maximized [28].

After estimating the regression coefcients, they are interpreted. Compared to linear regression, the regression coefcients of logistic regression are more diffcult to interpret, as there is no linear relationship between the infuencing variables and the probabilities. To determine more than just the direction of the infuence of the independent variables, the ratio of the probability of occurrence to the counter probability (1—p(y=1)) can be used instead of the probability of occurrence (p(y=1)). This ratio shows the odds of the event y=1 occurring compared to the event y=0. This can be expressed formally as follows:

odds .

Based on these odds, the odds ratio can be calculated:

odds ratio = .

Thus, the strength of the influence of the independent variables can be determined. If an independent variable is increased by one unit, the odds of the event y=1 occurring compared to the event y=0 change by a factor of . When the regression coefficient is positive, the odds ratio is greater than 1. If the regression coefficient is negative, the odds ratio is less than 1. If the odds ratio has the value 1.8, e.g., this means that the chance of y=1 occurring is 1.8 times as great as the chance of not occurring.

5 Findings and discussion

Section titled “5 Findings and discussion”The results of the two logistic regressions for each derived hypothesis are presented below. The two binary-coded variables click probability and purchase probability serve as dependent variables. The analyses were done with the statistical software SPSS. Before discussing the results of the logistic regression analysis, it is first necessary to ensure that the data set used meets the conditions for performing a logistic regression. With 823 observations, the sample meets the requirements for the sample size. The premise that the independent variables should be free of multicollinearity is also fulfilled in the research model. The correlation analysis shows no evidence of multicollinearity. In addition, an analysis was conducted to identify outliers. This revealed no indication of possible outliers.

Various statistical tests are used to test the overall model for goodness. For the first model with click probability as the dependent variable, a highly significant result was identified for the Omnibus test. This result ( ; p < 0.001) shows that the complete logistic model explains the data significantly better than the baseline model. This means that at least one predictor in the model contributes to the explanation of the dependent variable. The classification matrix was used to calculate the predictive accuracy by setting the correctly predicted cases in relation to the total number of cases. The classification accuracy is 91% and is higher than in the baseline model. In addition, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test shows whether there are significant differences between the expected and the observed values [28]. The results of the test ( ; p = 0.814) indicate that there is no significant difference, demonstrating a high goodness of fit. The values of the pseudo R-squared statistics (Cox and Snell-R2=0.314; Nagelkerke-R2=0.549) demonstrate a high goodness of fit.

Table 6 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis for click probability as the dependent variable. The table includes the estimated regression coefficients

Table 6 Results of the logistic regression analysis (click probability)

| Variable | bj | Standard error | Wald test | ebj | 95% confdence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Content-related design criteria | ||||||

| Keyword specifcity | 1.278 | .322 | 15.731** | 3.590 | 1.909 | 6.750 |

| Number of product details | −.737 | .233 | 10.010** | .478 | .303 | .755 |

| Formal design criteria | ||||||

| Number of characters | 012 | .025 | 0.235n.s | .988 | .940 | 1.038 |

| Keyword matching options | .460 | .312 | 2.169 n.s | 1.584 | .859 | 2.921 |

| Quality | .322 | .077 | 18.724** | 1.393 | 1.199 | 1.619 |

| Competition-related design criteria | ||||||

| Competition | −.036 | .049 | .536n.s | .965 | .876 | 1.062 |

| Distance of the bid | −1.501 | .184 | 66.865** | .223 | .155 | .319 |

| intercept | 2.427 | .061 | .230n.s | 11.325 |

** =signifcant at the 0.01 level; n.s.=not signifcant

(bj ), the standard errors, the values of the Wald test, the odds ratios (ebj ), and their 95% confdence intervals.

The combination of high values of the Wald statistic with small signifcance values shows that only the keyword specifcity, the number of product details, the quality and the distance of the bid have an infuence on the separation of the groups.

With regard to keyword specifcity, the results are signifcant. Since both the lower limit and the upper limit of the 95% confdence interval are above the value 1, the direction of the infuence of the keyword specifcity on the click can also be regarded as certain. With a signifcant ebj = 3.590 there is a strong positive infuence on the click probability. The more specifcally a product is described in a keyword, the higher the probability that a search engine user will click on the associated ad. This shows that restricting the product with the brand and further details increases the chance of being found and clicked on in the search results. This supports H1a. The previously assumed negative infuence of the number of product details on the click probability can be confrmed. With a signifcant result of ebj = 0.478, it can be seen that the number of product details reduces the click probability. This result can be explained by the fact that the higher the number of product details, the lower the search frequency of the keyword and therefore the lower the click probability of the keyword. H2a can therefore be supported. It can be stated that both content-related design criteria examined have a signifcant infuence on the click probability. However, it can also be seen that the more detailed description of a product within the keyword can have both positive and negative efects on the click probability. The crucial factor in this context is the specialization of the product via the brand and not via the number of product details.

With regard to the formal design criteria of this study, it can be seen that the number of characters has no signifcant infuence on the click probability. Since the upper and the lower limit of the 95% confdence interval are not both above or below

the value 1, the direction of the infuence cannot be interpreted. For this reason, H3a must be rejected. The results suggest that long-tail keywords are not automatically associated with higher quality. As the results regarding the number of characters and the expected higher click probability are not statistically signifcant, no clear conclusion can be drawn in favor of the long-tail principle. Instead, the results only show that a higher number of product details within the keywords leads to a reduction in click probability. So, while the addition of product details appears to have a negative efect on click behavior, it cannot be confrmed that longer keywords necessarily have a lower click probability. The keyword matching options are also part of the formal design. Even for this variable, the upper and the lower limit of the 95% confdence interval are not both below or above the value of 1. This means that the infuence of the keyword matching options on the click probability cannot be verifed and H4a must be rejected. In contrast, the quality of the keyword can be interpreted. With a signifcant odds ratio of ebj = 1.393, the positive infuence of keyword quality on click probability is evident. If the quality rating of the keyword improves by one unit, the click probability increases by 39.3%. H5a can therefore be supported. Nevertheless, it appears that the formal design criteria are of secondary importance compared to the content-related design criteria.

The competition of the keyword as one of the two competition-related design criteria shows no signifcant infuence on the click probability. H6a must therefore be rejected. The second competition-related variable, distance of the bid, shows a highly signifcant odds ratio of ebj = 0.223. If the distance between the bid for the keyword in relation to the average maximum bid increases by one unit, the probability of a click decreases by 77.7%. Hypothesis H7a can therefore be supported. For the competition-related design criteria, it can be summarized that the competition has no measurable infuence on the click probability. The distance of the bid from the average maximum bid has a strong negative infuence on the click probability of the keyword.

For the second logistic regression with purchase probability as the dependent variable, the same tests were conducted as for the previous analysis. A highly signifcant result was obtained for the omnibus test. The result of this test (χ2 (7)=174.393; p<0.001) indicates that the complete logistic model explains the data signifcantly better than the baseline model. The predictive accuracy was also calculated for this model using the classifcation matrix. The classifcation accuracy is 66% and is higher than in the baseline model. The results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2 (8)=12.266; p=0.140) show no signifcant diferences, which demonstrates a high goodness of ft. The values of the pseudo R-squared statistics (Cox and Snell-R2=0.191; Nagelkerke-R2=0.257) indicate a satisfactory goodness of ft.

Table 7 shows the results of the second logistic regression analysis. The table includes the estimated regression coefcients (bj ), the standard errors, the values of the Wald test, the odds ratios (ebj ), and their 95% confdence intervals.

As in the frst logistic regression analysis, keyword specifcity has a signifcant positive infuence. Since both the lower limit and the upper limit of the 95% confdence interval are above the value 1, the direction of the infuence can be regarded as certain. With a signifcant odds ratio of ebj = 1.502, there is a strong positive infuence of the keyword specifcity on the purchase probability.

Table 7 Results of the logistic regression analysis (purchase probability)

| Variable | bj | Standard error | Wald test | ebj | 95% confdence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Content-related design criteria | ||||||

| Keyword specifcity | .407 | .156 | 6.850** | 1.502 | 1.108 | 2.038 |

| Number of product details | −.903 | .151 | 35.949** | .406 | .302 | .545 |

| Formal design criteria | ||||||

| Number of characters | .034 | .012 | 7.749** | 1.035 | 1.010 | 1.060 |

| Keyword matching options | .321 | .169 | 3.633n.s | 1.379 | .991 | 1.919 |

| Quality | .322 | .060 | 29.180** | 1.380 | 1.228 | 1.550 |

| Competition-related design criteria | ||||||

| Competition | .021 | .028 | .561 n.s | 1.021 | .967 | 1.079 |

| Distance of the bid | −.226 | .110 | 4.224* | .798 | .643 | .990 |

| Intercept | −6.399 | 2.924 | 4.790* | .002 |

** =signifcant at the 0.01 level; *=signifcant at the 0.05 level; n.s.=not signifcant

Accordingly, H1b can be supported. The previously assumed negative infuence on the purchase probability can again be confrmed for the number of product details. With a signifcant odds ratio of ebj = 0.406, it can be seen that the number of product details reduces the purchase probability. Adding a further product detail to the keyword reduces the probability that a search engine user will buy the advertised product by 59.4%. H2b is therefore supported.

With regard to the formal design criteria of the purchase probability analysis, the odds ratio for the number of characters is ebj = 1.035. This very small value shows that the number of characters has only a minor infuence on the purchase probability. Since a negative infuence of the number of characters on the purchase probability was previously assumed, H3b must be rejected. A possible explanation can be found in the fact that although transactional keywords are often associated with a higher character count, these can arise due to specifc search terms or long product and brand names. This means that the number of characters cannot be explicitly equated with an advanced search by the search engine user. The keyword matching options show no signifcant infuence on the purchase probability. H4b must therefore be rejected. The third formal design criterion examined is the quality of the keyword. With a signifcant odds ratio of ebj = 1.380, the positive infuence of the quality of the keyword on the purchase probability is demonstrated. If the quality rating of the keyword improves by one unit, the probability of a purchase increases by 38%. Thus, H5b is supported. In summary for the formal design criteria, it can be stated that the keyword matching options do not infuence the purchase probability and the number of characters only has a marginal infuence. Only the quality of the keyword has a clearly positive infuence on the purchase probability. Even in terms of purchase probability, the formal design criteria appear to be less important than the contentrelated criteria.

As part of the competition-related criteria, the competition of the keyword was frst examined in relation to the purchase probability. However, the results show no signifcant infuence of the keyword’s competition. For this reason, H6b must be rejected. For the independent variable distance of the bid, an odds ratio of ebj = 0.798 is observed. If the distance between the bid for the keyword in relation to the average maximum bid increases by one unit, the probability of a purchase decreases by 20.2%. Thus, H7b is supported. In summary, the investigation of competitionrelated design criteria has shown that competition has no demonstrable infuence on the purchase probability. However, the distance of the bid has a signifcantly negative impact on the purchase probability of the keyword. Nevertheless, this impact is considerably smaller than the infuence of this variable on the click probability.

6 Conclusion

Section titled “6 Conclusion”6.1 Theoretical and managerial implications

Section titled “6.1 Theoretical and managerial implications”The outcomes of this study yield novel and valuable insights pertinent to both academics and practitioners concerning the impact of diverse keyword design criteria on the two target variables: click probability and purchase probability. In summary, it can be stated that the determinants keyword specifcity, number of product details, quality and distance of the bid have a statistically signifcant infuence on both the click probability and the purchase probability. Concerning the theoretical contribution, the results show that the phases of the buyer’s journey should be considered in keyword design. As potential customers are in diferent decision-making stages, the requirements for keywords vary depending on the phase. In the awareness phase, informative and problem-oriented keywords are particularly relevant to generate attention. In the consideration phase, comparative and solution-oriented keywords become more important, while in the decision phase, the focus is on transactionrelated keywords that signal a clear intention to buy. The various design criteria are therefore of varying relevance in the phases of the buyer’s journey.

In terms of click probability, the keyword specifcity and the keyword quality have a positive infuence, while negative infuences are associated with the number of product details and the distance of the bid. In contrast, the study found no statistically signifcant efects for the number of characters, keyword matching options and competition on click probability. For companies that initially focus on maximizing visibility through search engine advertising, it is advisable to increase the probability of clicks. This can be achieved by carefully defning keywords where products are closely associated with brands and product-related details. Regarding the buyer’s journey, these design criteria would be especially relevant to reach users who are in the awarness phase and thus still at the beginning of their search. Another way to increase the click probability is to improve keyword quality. Even this design criterion is particularly important in the awarness phase. Advertisers can achieve a higher quality, for example, by improving the user-friendliness of their website or matching the ad texts to the keywords. The landing page experience should also be optimized with clear, relevant content and fast page loading times. Conversely,

overloading the keywords with a series of product details should be avoided. As the analysis has shown, adding the brand to the product type signifcantly improves the click probability, while many non-brand product details reduce the click probability. Advertisers should focus on the essential product features instead of including a large number of technical specifcations. With the help of A/B tests with diferently detailed keywords, an attempt could be made to determine the optimum level of product information. Likewise, maintaining an optimal distance between the click price and the average maximum bid for the keyword is crucial. Undercutting the average maximum bid poses a risk of substantial reduction in click probability. A reduction in the advertiser’s bid for a particular keyword can result in a lower or non-existent ad display, which can reduce the click probability to zero in extreme cases. Particularly in the frst phase of the buyer’s journey, when users are not yet searching specifcally, reducing the bid too much compared to the average maximum bid can result in users’ awareness not being gained.

As it is equally important for vendors to stimulate product purchases through advertising, the keyword design criteria were analyzed concerning their impact on purchase probability. The analysis revealed largely similar infuences of keyword design criteria on purchase probability as observed in click probability. Specifcally, keyword specifcity, the number of characters, and keyword quality signifcantly infuence the purchase probability positively. The number of product details and the distance of the bid afect the purchase probability signifcantly negative. In contrast to the study on click probability, the second logistic regression showed a small positive infuence of the number of characters on the purchase probability. One possible explanation lies in the fact that transactional keywords, in particular, tend to be considerably longer than generic keywords, which refects the increasing specifcity of search queries with increasing purchase intent. A higher keyword specifcity and a larger number of characters are important in the consideration and decision phase of the buyer’s journey. As users compare alternatives and come to a decision, longer and more specifc keywords are helpful. Advertisers are advised to use more specifc keywords to achieve higher purchase probabilities. It should be ensured that long keywords remain easy to read and are not cut of by truncation. Nevertheless, in the last two phases of the buyer’s journey, advertisers should also pay attention to high keyword quality and not let the distance between the bid and the average maximum bid become too large. In this context, the efectiveness of the bidding strategy depends not only on the amount of the bid itself, but also on how well it is matched to the phase of the user’s buyer’s journey and thus to the average maximum bid.

No signifcant infuence on either click or purchase probability was evidenced for the keyword matching options and competition in both analyses. It can be assumed that these variables are of minimal importance regarding the target variables. Consequently, less emphasis should be placed on both criteria when designing keywords. Advertisers should therefore concentrate on exact and phrase-based matches in order to avoid irrelevant clicks. Although the intensity of competition should continue to be monitored, a stronger focus should be placed on own keyword relevance and on quality signals. Advertisers are advised to consider content-related design criteria, keyword quality, and the distance of the bid to the average maximum bid of the keyword. By actively factoring the distance of the bid into their bidding strategy,

advertisers can identify keywords where their bids are signifcantly lower than the competitive average, uncovering untapped potential. Targeted bid adjustments increasing bids for strategically important keywords or lowering them for less efcient ones—allow for a more efective budget allocation, improved auction visibility, and a sustainable increase in reach and conversion quality.

6.2 Limitations and further research

Section titled “6.2 Limitations and further research”While the study provides valuable insights into the factors infuencing the probability of search engine users clicking on a paid ad or making a purchase through it, it is not without its limitations. Firstly, the empirical results are based on data sourced exclusively from a single online retailer. Although a transfer of the results is obvious, it should nevertheless be validated with further data from diferent sectors. Even if the study has already examined important parameters of search engine advertising with the target variables click and purchase probability, the investigation of the keyword design criteria could also be performed using monetary target variables. Such an examination would be relevant to determine how the infuence of keyword design criteria may vary in relation to these monetary metrics.

In view of the rapid development of AI, it would also be relevant to investigate how AI-supported algorithms change the efectiveness of traditional keyword optimization strategies. For example, a comparison of the efect of manually created vs. AI-generated keywords in terms of click and purchase probabilities would be conceivable. It would also be interesting to explore how AI can predict user intention even more precisely and what impact this has on the choice of keywords. Another current development is the increasing use of voice assistants. A study could investigate the infuence of changed user search queries on search engine advertising and keyword optimization in particular. Longer, conversational and question-based keywords could become more important as a result of voice search.

References

Section titled “References”-

1. Abhishek, V. & Hosanagar, K. (2007). Keyword Generation for Search Engine Advertising using Semantic Similarity between Terms. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Electronic Commerce, Minneapolis, USA, pp. 89–94.

-

2. Abhishek, V., & Hosanagar, K. (2013). Optimal bidding in multi-item multislot sponsored search auctions. Operations Research, 61(4), 855–873.

-

3. Abou Nabout, N., & Skiera, B. (2012). Return on quality improvements in search engine marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(3), 141–154.

-

4. Agarwal, A., Hosanagar, K., & Smith, M. D. (2011). Location, location, location: an analysis of proftability of position in online advertising markets. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(6), 1057–1073.

-

5. Amaldoss, W., Jerath, K., & Sayedi, A. (2016). Keyword management costs and ‘broad match’ in sponsored search advertising. Marketing Science, 35(2), 259–274.

-

6. Anderson, C. (2006). The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. Hyperion.

-

7. Andersson, S., Aagerup, U., Svensson, L., & Eriksson, S. (2024). Challenges and opportunities in the digitalization of the B2B customer journey. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 39(13), 160–174.

-

8. Animesh, A., Viswanathan, S., & Agarwal, R. (2011). Competing ‘creatively’ in sponsored search markets: The efect of rank, diferentiation strategy, and competition on performance. Information Systems Research, 22(1), 153–169.

-

9. Atkinson, G., Driesener, C., & Corkindale, D. (2014). Search engine advertisement design efects on click-through rates. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 14(1), 24–30.

-

10. Blankenbaker, J., & Mishra, S. (2009). Paid search for online travel agencies: Exploring strategies for search keywords. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 8(2/3), 155–165.

-

11. Broder, A. Z., Fontoura, M., Gabrilovich, E., Joshi, A., Josifovski, V., & Zhang, T. (2007). Robust Classifcation of Rare Queries Using Web Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Amsterdam, Niederlande, pp. 231–238.

-

12. Cao, X., Yang, Z., Wang, F., Lu, C., & Wu, Y. (2021). From keyword to keywords – the role of keyword portfolio variety and disparity in product sales. Asia Pacifc Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(6), 1285–1302.

-

13. Chen, H.-Y., & Lo, T.-C. (2019). Online search activities and investor attention on fnancial markets. Asia Pacifc Management Review, 24(1), 21–26.

-

14. Çokluk, Ö. (2010). Logistic regression: Concept and application. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 10(3), 1397–1407.

-

15. DeMaris, A. (1995). A tutorial in logistic regression. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(4), 956–968.

-

16. Desai, P. S., Shin, W., & Staelin, R. (2014). The company that you keep: When to buy a competitor’s keyword. Marketing Science, 33(4), 485–508.

-

17. Dhar, V., & Ghose, A. (2010). Research commentary: Sponsored search and market efciency. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 760–772.

-

18. Du, X., Su, M., Zhang, X., & Zheng, X. (2017). Bidding for multiple keywords in sponsored search advertising: Keyword categories and match types. Information Systems Research, 28(4), 711–722.

-

19. Easley, D., & Kleinberg, J. (2010). Networks, crowds, and markets: Reasoning about a highly connected world. Cambridge University Press.

-

20. Edelman, B., & Ostrovsky, M. (2007). Strategic bidder behavior in sponsored search auctions. Decision Support Systems, 43, 192–198.

-

21. Feng, J., Bhargava, H. K., & Pennock, D. M. (2007). Implementing sponsored search in web search engines: Computational evaluation of alternative mechanisms. Informs Journal on Computing, 19(1), 137–148.

-

22. Fuchs, T., Zilling, M. P., & Schüle, H. (2012). Analyse des Spillover-Efekts in Suchketten anhand des Google Conversion Tracking. PFH Research Papers No. 2012/08.

-

23. Gajanova, L. (2021). The Agile content marketing roadmap based on the B2B Buyer’s journey – the case study of the Slovak republic. SHS Web of Conferences, 91(01025), 1–9.

-

24. Geddes, B. (2014). Advanced Google Adwords (3rd ed.). Sybex.

-

25. Ghose, A., & Yang, S. (2009). An empirical analysis of search engine advertising: Sponsored search in electronic markets. Management Science, 55(10), 1605–1622.

-

26. Google Ads Help (2022). Keywords: Defnition. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://support. google.com/google-ads/answer/6323?hl=en

-

27. Google Ads Help (2023). About Quality Score. Retrieved January 9, 2023, from https://support. google.com/google-ads/answer/6167118?hl=en

-

28. Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2013). Applied Logistic Regression (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

-

29. Huang, S.-L., & Lin, Y.-H. (2022). Exploring consumer online purchase and search behavior: An FCB grid perspective. Asia Pacifc Management Review, 27(4), 245–256.

-

30. Humphreys, A., Isaac, M. S., & Wang, R. J. (2021). Construal matching in online search: Applying text analysis to illuminate the consumer decision journey. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(6), 1101–1119.

-

31. IAB/PWC (2022). IAB Internet Advertising Revenue Report: 2022 Full Year Results. Retrieved September 6, 2023, from https://www.iab.com/insights/internet-advertising-reven ue-report-full-year-2022/

-

32. Jansen, B. J., Liu, Z., & Simon, Z. (2013). The efect of ad rank on the performance of keyword advertising campaigns. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(10), 2115–2132.

-

33. Jansen, B. J., & Schuster, S. (2011). Bidding on the buying funnel for sponsored search and keyword advertising. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(1), 77–106.

-

34. Jansen, B. J., Sobel, K., & Zhang, M. (2011). The brand efect of key phrases and advertisements in sponsored search. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 12(1), 1–18.

-

35. Ji, L., Rui, P., & Hansheng, W. (2010). Selection of best keywords. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 11(1), 27–35.

-

36. Kakalejčík, L., Bućko, J., & Vejačka, M. (2019). Diferences in buyer journey between high- and low-value customers of E-commerce business. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 14(2), 47–58.

-

37. Klapdor, S., Anderl, E. M., von Wangenheim, F., & Schumann, J. H. (2014). Finding the right words: The infuence of keyword characteristics on performance of paid search campaigns. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(4), 285–301.

-

38. Kritzinger, W. T., & Weideman, M. (2013). Search engine optimization and pay-per-click marketing strategies. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 23(3), 273–286.

-

39. Li, H., Kannan, P. K., Viswanathan, S., & Pani, A. (2016). Attribution strategies and return on keyword investment in paid search advertising. Marketing Science, 35(6), 831–848.

-

40. Lu, X., & Zhao, X. (2014). Diferential efects of keyword selection in search engine advertising on direct and indirect sales. Journal of Management Information Systems, 30(4), 299–325.

-

41. Nagpal, N., & Petersen, J. A. (2021). Keyword selection strategies in search engine optimization: How relevant is relevance. Journal of Retailing, 97(4), 746–763.

-

42. Narayanan, S., & Kalyanam, K. (2015). Position efects in search advertising and their moderators: A regression discontinuity approach. Marketing Science, 34(3), 388–407.

-

43. Nottorf, F., Mastel, A. & Funk, B. (2012). The user-journey in online search: An empirical study of the generic-to-branded spillover efect based on user-level data. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Communication Networking, e-Business and Optical Communication Systems, Rome, Italy, pp. 145–153.

-

44. Nuseir, M. T. (2019). The impact of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) on the online purchase intention of consumers in the Islamic countries – a case of (UAE). Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(3), 759–767.

-

45. Rutz, O. J., & Bucklin, R. E. (2011). From generic to branded: A model of spillover in paid search advertising. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(1), 87–102.

-

46. Rutz, O. J., Trusov, M., & Bucklin, R. E. (2011). Modeling indirect efects of paid search advertising: Which keywords lead to more future visits? Marketing Science, 30(4), 646–665.

-

47. Simonov, A., Nosko, C., & Rao, J. M. (2018). Competition and crowd-out for brand keywords in sponsored search. Marketing Science, 37(2), 200–215.

-

48. Skiera, B., Eckert, J., & Hinz, O. (2010). An analysis of the importance of the long tail in search engine marketing. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(6), 488–494.

-

49. Talwar, R., & Upadhyaya, S. (2017). Long tail keyword suggestion for sponsored search advertising. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 4(7), 1407–1413.

-

50. Urban, D. (1993). Logit-analyse: Statistische Verfahren zur Analyse von Modellen mit qualitativen Response-Variablen. De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

-

51. Varian, H. R. (2009). Online Ad Auctions. American Economic Review, 99(2), 430–434.

-

52. Vangelov, N. (2020). Managing key performance indicators for successful online advertising campaigns. In: Communication Management: Theory and Practice in the 21st Century, Valkanova, Bulgarien, pp. 219–227.

-